מקורותיו של סִינִית מִטְבָּח ניתן לאתר אלפי שנים. המטבח הסיני מגוון ביותר עם וריאציות אזוריות רחבות, ולא נדיר שאפילו הסינים עצמם מוצאים את המטבח מאזור אחר להיות זר לחלוטין עבורם. צפון סינים עשויים לדמיין שהמטבח הקנטונזי מורכב מביצים מוקפצות בלבד עם עגבנייה, ואילו הדרומיים עשויים להיות נדהמים מגודל הכופתאות המוגשות בצפון סין.

מבינה

| “ | אזרחים הם הבסיס לממשל של מלך, ואילו אוכל הוא הבסיס לחיי אזרח. | ” |

—באן גו, ספר האן, כרך 43 | ||

דרך סין הקיסרית, התרבות הסינית השפיעה על ארצות כמו של ימינו מונגוליה ו וייטנאם. המטבח הסיני כבר ידוע מזה זמן רב במדינות אסיאתיות אחרות כמו קוריאה ו יפן.

בתקופה המודרנית הפזורה הסינית הפיצה את המטבח הסיני לחלקים רחוקים יותר של העולם. עם זאת, חלק גדול מכך הותאם לתנאים המקומיים, כך שלעתים קרובות תמצאו מנות בקהילות סיניות מעבר לים שלא ניתן למצוא בסין, או שהשתנו במידה ניכרת מגרסאותיהן הסיניות המקוריות. מלזיה, תאילנד, וייטנאם ו סינגפור במיוחד הם מקומות מצוינים לטעום מאכלים כאלה בשל ההיסטוריה הארוכה של הקהילות הסיניות שם והטעימות של מרכיבים מקומיים ושיטות בישול מסורתיות. לעומת זאת, לסינים שחזרו מעבר לים הייתה השפעה גם על הסצינה הקולינרית של המולדת, אולי באופן המורגש ביותר גואנגדונג, פוג'יאן ו היינאן.

בערים רבות במדינות המערב יש צ'יינה טאון רובע, ואפילו בעיירות קטנות יותר יש לעתים קרובות כמה מסעדות סיניות. במקומות אלה תמיד היה אוכל קנטונזי בעיקר, אך סגנונות אחרים הפכו נפוצים יותר.

המטבח הסיני יכול לנוע בין אוכל רחוב פשוט אך לבבי לסעודות המשובחות המובילות, תוך שימוש במרכיבים היוקרתיים ביותר, עם מחירים שתואמים. הונג קונג נחשב בדרך כלל למרכז הסיני העיקרי בעולם אוכל משובחלמרות זאת סינגפור ו טייפה הם גם לא סליחים, והערים הסיניות ביבשת של שנחאי ו בייג'ינג גם מתעדכנים לאט אבל בטוח.

זמן אוכל בסין הם בצד המוקדם ככל שהמדינות מתקרבות - קרוב יותר לזמני הארוחות בארה"ב מאשר לארוחות האירופיות. ארוחת הבוקר היא בדרך כלל בין השעות 07:00 ל -09: 00, והיא כוללת לעיתים קרובות דברים כמו אטריות, לחמניות מאודות, קונגי, מאפים מטוגנים, חלב סויה, ירקות או כופתאות. זמן השיא לארוחת הצהריים הוא 12: 00-13: 00, וארוחת הערב היא לעתים קרובות איפשהו בסביבות 17: 30-19: 30.

מאכלים אזוריים

המטבח הסיני משתנה במידה רבה, תלוי באיזה חלק של המדינה אתה נמצא. "ארבעת המטבחים הגדולים" (四大 菜系) הם סצ'ואן (צ'ואן), שאנדונג (Lu), גואנגדונג (קנטונזית / יואה), ו ג'יאנגסו מאכלים (Huaiyang), ואזורים אחרים הם בעלי סגנונותיהם, עם מסורות קולינריות שונות במיוחד באזורי מיעוטים אתניים כגון טיבט ו שינג'יאנג.

לא קשה לטעום כמה מהמטבחים האזוריים חרסינה גם אם אתה רחוק מאזורי מוצאם - סצ'ואנים מאלה (麻辣) אוכל חריף עקצני ניתן למצוא בכל מקום, למשל, כמו גם שלטי פרסום לנזו אטריות (兰州 拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn). באופן דומה, למרות שברווז הפקין (北京 烤鸭) הוא לכאורה מומחיות מקומית של בייג'ינג, הוא זמין באופן נרחב גם במסעדות קנטונזיות רבות.

- בייג'ינג (京 菜 ג'ינג קאי ): אטריות ביתיות ו באוזי (包子 לחמניות לחם), ברווז פקין (北京 烤鸭 Běijīng Kǎoyā), אטריות רוטב מטוגן (炸酱面 zhájiàngmiàn), מנות כרוב, חמוצים נהדרים. יכול להיות טעים ומשביע.

- אימפריאלי (宫廷菜 Gōngtíng Cài): ניתן לטעום את האוכל של בית המשפט הצ'ינג המנוח, שהתפרסם על ידי הקיסרית הבוגרת סיקסי, במסעדות מתמחות יוקרתיות בבייג'ינג. המטבח משלב אלמנטים של אוכל גבול של מנצ'ו כמו בשר צבי עם אקזוטיקה ייחודית כמו כף הגמל, סנפיר הכריש וקן הציפורים.

- קנטונזית / גואנגזו / הונג קונג (广东 菜 Guǎngdōng Cài, 粤菜 יואי קאי): הסגנון שרוב המבקרים המערביים כבר מכירים (אם כי בצורה מקומית). לא חריף מדי, הדגש הוא על מרכיבים טריים ופירות ים. עם זאת, המטבח הקנטונזי האותנטי הוא גם בין ההרפתקנים בסין מבחינת מגוון המרכיבים, שכן הקנטונזים מפורסמים, אפילו בקרב הסינים, בזכות הגדרתם הרחבה ביותר של מה שנחשב למאכל.

- דים סאם (点心 דינקסין במנדרין, דימסאם בקנטונזית), חטיפים קטנים שאוכלים בדרך כלל בארוחת הבוקר או בארוחת הצהריים, הם גולת הכותרת.

- בשרים קלויים (烧 味 שאוואי במנדרין, sīuméi בקנטונזית) פופולריים גם במטבח הקנטונזי, הכולל כמה מנות פופולריות בצ'יינה טאונס במערב כמו ברווז צלוי (烧鸭 שאויא במנדרין, sīu'aap בקנטונזית), עוף רוטב סויה (豉 油 鸡 chǐyóujī במנדרין, sihyàuhgāi בקנטונזית), חזיר צלוי (叉烧 צ'אשאו במנדרין, chāsīu בקנטונזית) ובטן חזיר עור פריך (烧肉 שאורו במנדרין, sīuyuhk בקנטונזית).

- בשרים נרפא (腊味 לאווי במנדרין, laahpméi בקנטונזית) הם מומחיות נוספת של המטבח הקנטונזי, וכוללת נקניקיות סיניות (腊肠 làcháng במנדרין, laahpchéung בקנטונזית), נקניקיות כבד (膶 肠 rùncháng במנדרין, יונצ'ונג בקנטונזית) וברווז משומר (腊鸭 לאיה במנדרין, לאהפ'אאפ בקנטונזית). דרך נפוצה לאכול אותם היא בצורה של אורז חרסית בשר נרפא (腊味 煲仔饭 làwèi bāozǎi fàn במנדרין, laahpméi bōujái faahn בקנטונזית).

- קונגי (粥 zhōu במנדרין, ג'וק בקנטונזית) פופולרי גם במטבח הקנטונזי. הסגנון הקונגונזי של הקונג'י כולל שהאורז מבושל עד שהדגנים כבר לא נראים לעין, ויש בו מרכיבים אחרים כמו בשרים, פירות ים או קטלנים המבושלים עם האורז על מנת לטעום את הקונגי.

- Huaiyang (淮揚菜 Huáiyáng Cài): המטבח של שנחאי, ג'יאנגסו ו ג'ג'יאנג, הנחשב לתערובת טובה של סגנונות בישול בצפון ובדרום סין. המנות המפורסמות ביותר הן קסיאולונגבאו (小笼 包 Xiǎolóngbāo) כופתאות עירית (韭菜 饺子 Jiǔcài Jiǎozi). מנות חתימה אחרות כוללות בטן חזיר מושחתת (红烧肉 הונג שאו רו) וצלעות חזיר מתוקות (糖醋 排骨 táng cù pái gǔ). סוכר מתווסף לעיתים קרובות למנות מטוגנות ומעניק להם טעם מתוק. אף על פי שהמטבח השנגחאי נחשב לעיתים קרובות כמייצג את הסגנון הזה, למטבחים של הערים הסמוכות כמו האנגג'ואו, סוז'ו וננג'ינג יש מאכלים וטעמים ייחודיים משלהם ובהחלט שווה לנסות גם.

- סצ'ואן (川菜 צ'ואן קאי): חם ומתובל להפליא. אמירה פופולרית היא שזה כל כך חריף שהפה שלך יהיה קהה. עם זאת, לא כל המנות מיוצרות עם צ'ילי חי. התחושה המרדמת מגיעה למעשה מפלפל הסצ'ואן (花椒 huājiāo). זה זמין באופן נרחב מחוץ לסצ'ואן וגם יליד צ'ונגקינג. אם אתם רוצים אוכל סצ'ואני אותנטי באמת מחוץ לסצ'ואן או צ'ונגצ'ינג, חפשו בתי אוכל קטנים המסמנים את הדמויות למטבח הסצ'ואני בשכונות עם הרבה מהגרי עבודה. אלה נוטים להיות הרבה יותר זולים ולעתים קרובות טובים יותר ממסעדות סצ'ואן השונות בכל מקום.

- הונאן (湖南菜 הוניאן קאי, 湘菜 שינג קאי): המטבח של אזור שיאנג-ג'יאנג, אגם דונגטינג ומערב פרובינציית הונאן. דומה, מבחינות מסוימות, למטבח הסצ'ואני, הוא יכול להיות "חריף יותר" במובן המערבי.

- Teochew / Chiuchow / Chaozhou (潮州菜 צ'אוז'ו קאי): שמקורם ב צ'אושאן אזור במזרח גואנגדונג, סגנון ייחודי אשר בכל זאת יהיה מוכר לרוב הסינים בדרום מזרח אסיה והונג קונג. המאכלים המפורסמים כוללים ברווז מבושל (卤鸭 Lǔyā), קינוח הדבקת ים (芋泥 יוני) וכדורי דגים (鱼丸 יואן).

- דייסת אורז (粥 zhōu במנדרינית, 糜 muê5 ב- Teochew) היא מנת נוחות במטבח ה- Teochew. בשונה מהגרסה הקנטונזית, גרסת Teochew משאירה את גרגרי האורז שלמים. דייסת טיוצ'ו מוגשת בדרך כלל רגילה עם מנות מלוחות אחרות בצד, אם כי דייסת דגים של טיוצ'ו מכילה לעתים קרובות את האורז מבושל במרק דגים ומבושל עם פרוסות דגים.

- האקה / קייג'יה (客家 菜 Kèjiā Cài): המטבח של אנשי האקה, המפוזר באזורים שונים בדרום סין. מתמקדת בבשר וירקות משומרים. מנות מפורסמות כוללות טופו ממולא (酿 豆腐 niàng dòufǔ, ממולא בבשר כמובן), מלון מריר ממולא (酿 苦瓜 niàng kǔguā, גם ממולא בבשר), חזיר ירוק חרדל מוחמץ (梅菜 扣肉 méicài kòuròu), חזיר מכוסה עם טארו (芋头 扣肉 yùtóu kòuròu), עוף אפוי במלח (盐 焗 鸡 yánjújī) ותה טחון (擂茶 léi chá).

- פוג'יאן (福建 菜 פוג'יאן קאי, 闽菜 Mǐn Cài): משתמש במרכיבים בעיקר ממימי מים חוףיים ושפכים. ניתן לפצל את המטבח הפוג'יאני לשלושה מאכלים נפרדים לפחות: דרום פוג'יאן מִטְבָּח, פוז'ו מטבח, ו מערב פוג'יאן מִטְבָּח.

- דייסת אורז (粥 ז'ו במנדרינית, 糜 לִהיוֹת במינן) הוא מאכל פופולרי בדרום פוג'יאן. זה דומה לגרסת Teochew, אך בדרך כלל מבושל עם פרוסות בטטה. זה מאוד פופולרי גם בטייוואן, שם זו מנת ארוחת בוקר בסיסית.

- גויג'ואו (贵州 菜 Guìzhōu Cài, 黔菜 צ'יאן קאי): משלב אלמנטים ממטבח סצ'ואן ושיאנג, תוך שימוש ליברלי בטעמים חריפים, פלפלים וחמצמצים. המוזר ז'רגן (折耳根 Zhē'ěrgēn), ירק שורש אזורי, מוסיף טעם חמוץ-פלפל בלתי ניתן לטעות למנות רבות. מנות מיעוט כמו סיר חם דגים חמוץ (酸汤鱼 סואן טאנג יו) נהנים מאוד.

- ג'ג'יאנג (浙菜 ז'ה קאי): כולל את המזונות של האנגג'ואו, נינגבו ושאוקסינג. תערובת מתובלת ועדינה של פירות ים וירקות המוגשת לעיתים קרובות במרק. לפעמים ממתקים קלות או לפעמים חמוץ מתוק, מנות ג'ג'יאנג כוללות לעתים קרובות בשר וירקות מבושלים בשילוב.

- היינאן (琼 菜 צ'יונג קאי): מפורסם בקרב הסינים, אך עדיין לא ידוע יחסית לזרים, המאופיין בשימוש כבד בפירות ים וקוקוסים. התמחויות החתימה הן "ארבע המנות המפורסמות של היינאן" (海南 四大 名菜 Hǎinán Sì Dà Míngcài): עוף וונצ'נג (文昌鸡 וונצ'נג ג'י), עז דונגשאן (东 山羊 Dōngshān yáng), ברווז ג'יאג'י (加 积 鸭 ג'יאג'י יא) וסרטן ההלה (和 乐 蟹 הלה קסי). בסופו של דבר עוף וונצ'אנג יוליד אורז עוף הינאני בסינגפור ובמלזיה, קאו מאן קאי (ข้าวมัน ไก่) בתאילנד, ו Cơm gà Hải Nam בווייטנאם.

- צפון מזרח סין (东北 דונגביי) יש סגנון אוכל משלו. זה שם דגש על חיטה על אורז וכמו צפון מערב, כולל לחמים שונים ומנות אטריות בתוספת קבבים (串 צ'ואן; שימו לב איך הדמות נראית כמו קבב!). האזור מפורסם במיוחד בזכות ג'יוזי (饺子), סוג של כופתאות שקשור קשר הדוק ליפנים גיוזה ודומה לרביולי או לפרוגיות. לערים רבות דרומית יותר יש ג'יאוזי מסעדות, ורבות מהן מנוהלות על ידי אנשי דונגביי.

המטבחים של הונג קונג ו מקאו הם בעצם המטבח הקנטונזי, אם כי עם השפעות בריטיות ופורטוגזיות בהתאמה, בעוד שהמטבח של טייוואן דומה לזה של דרום פוג'יאן, אם כי עם השפעות יפניות, כמו גם השפעות מאזורים אחרים בסין, הנובעות ממתכונים שהובאו על ידי לאומנים שברחו מהיבשת בשנת 1949. עם זאת, בעוד שפים מפורסמים רבים נמלטו מסין היבשת להונג קונג וטייוואן בעקבות זאת של המהפכה הקומוניסטית, אוכלים איכותיים ממקומות שונים בסין זמינים גם באזורים אלה.

רכיבים

שבעת הצרכים על פי אמירה סינית ישנה, ישנם שבעה דברים שאתה צריך כדי לפתוח את דלתותיך (ולנהל משק בית): עֵצֵי הַסָקָה, אורז, שמן, מלח, רוטב סויה, חומץ, ו תה. כמובן שעצי הסקה אינם כמעט הכרח בימינו, אך ששת האחרים נותנים תחושה אמיתית של עיקרי המפתח בבישול הסיני. שימו לב שפלפלי צ'ילי וסוכר אינם מגיעים לרשימה, למרות חשיבותם בכמה מאכלים סיניים אזוריים. |

- בָּשָׂר, במיוחד חזיר, נמצא בכל מקום. עופות כמו ברווז ועוף הם גם פופולריים, ולא חסר בשר בקר. טלה ועז פופולריים בקרב מוסלמים ובכלל במערב סין. אם אתה יודע לאן ללכת, אתה יכול גם לטעום בשרים יוצאי דופן יותר כמו נחש או כלב.

- חזיר - בעוד שאותו חזיר אירופי ואמריקאי עשויים להיות מוכרים יותר בעולם, סין היא גם מדינה מסורתית המייצרת בשר חזיר, עם כמה מהאבות היוקרתיים שלה עם היסטוריות שתוארכו מאות שנים ואפילו אלפי שנים. בשר חזיר סיני בדרך כלל מרפא יבש, ולעתים קרובות הוא משמש כבסיס מרק, או כמרכיב במגוון מאכלים. החזיר המהולל ביותר בסין הוא חזיר ג'ינהואה (金華 火腿 jīn huá huǒ tuǐ) מהעיר ג'ינחואה ב ג'ג'יאנג מָחוֹז. מלבד חזיר ג'ינחואה, חזיר רוגאו (如皋 火腿 rú gāo huǒ tuǐ) מהרוגאו ב ג'יאנגסו פרובינציה, ו Xuanwei חזיר (宣威 火腿 xuān wēi huǒ tuǐ) מ Xuanwei ב יונאן המחוז מגבש את "שלושת האמס הגדולים" של סין. חזיר מפורסם אחר כולל חזיר אנפו (安福 火腿 ān fú huǒ tuǐ) מאנפו ג'יאנגשי פרובינציה, שהוצגה בתערוכה הבינלאומית של פנמה – פסיפיק בשנת 1915, וחם נודנג (诺 邓 火腿 nuò dèng huǒ tuǐ) מ- Nuodeng שבמחוז יונאן, המהווה מומחיות של המיעוט האתני באי.

- אורז הוא המזון הבסיסי הארכיטיפי, במיוחד בדרום סין.

- נודלס הם גם מצרך חשוב, כאשר אטריות חיטה (面, miàn) נפוצות יותר בצפון סין ואטריות אורז (粉, fěn) נפוצות יותר בדרום.

- ירקות הם בדרך כלל מאודים, כבושים, מוקפצים או מבושלים. הם נאכלים לעתים נדירות גולמיים. לרבים יש שמות מרובים והם מתורגמים ומתורגמים בצורה שונה בדרכים שונות, מה שגורם לבלבול רב כשמנסים להבין הגיוני בתפריט. כמה מועדפים כוללים חצילים, יורה אפונה, שורש לוטוס, daikon ו יורה במבוק. הדלועים כוללים Calabash, מלון מר, דלעת, מלפפון, דלעת ספוג ומלון חורף. ירקות עלים מגוונים, אך רבים מהם אינם מוכרים פחות או יותר לדוברי האנגלית וניתן לתרגם אותם כמין כרוב, חסה, תרד או ירוק. כך תמצאו כרוב סיני, חסה ארוכה עלים, תרד מים וירקות בטטה, עד כמה שם.

- פטריות - המון סוגים שונים, החל מ"אוזן עץ "שחורה וגומי ועד" פטריות מחט זהובות "לבנות.

- טופו בסין זה לא רק תחליף לצמחונים, אלא פשוט אוכל אחר, המוגש לעיתים קרובות מעורבב עם ירקות, בשר או ביצים. זה מגיע במספר צורות שונות, שרבות מהן לא יהיו ניתנות לזיהוי אם אתה פשוט רגיל לגושים הלבנים המלבניים שזמינים ברחבי העולם.

מאכלים סיניים מסוימים מכילים מרכיבים שאנשים מסוימים מעדיפים להימנע מהם, כגון כלבים, חתולים, נחש או מינים בסכנת הכחדה. עם זאת, זה כן מאוד לא סביר שתזמין את המנות האלה בטעות. בדרך כלל מגישים כלב ונחש במסעדות מיוחדות שאינן מסתירות את מרכיביהן. ברור שמוצרים המיוצרים ממרכיבים בסכנת הכחדה יהיו במחירים אסטרונומיים וממילא לא היו רשומים בתפריט הרגיל. גם הערים של שנזן ו ג'והאי אסרו על אכילת בשר חתולים וכלבים, ואיסור זה מתוכנן להוארך בפריסה ארצית.

כמו כן, לפי התפיסה של הרפואה הסינית המסורתית, אכילת יותר מדי כלבים, חתולים או נחש אמורה לגרום לתופעות לוואי, ולכן הם לא נאכלים לעתים קרובות על ידי סינים.

באופן כללי, אורז הוא מצרך העיקרי בדרום, ואילו חיטה, בעיקר בצורת אטריות, היא מצרך העיקרי בצפון. מצרכים אלה קיימים תמיד, ואתה עלול לגלות שאתה לא מבלה יום אחד בסין בלי לאכול אורז, אטריות או שניהם.

לחם כמעט ולא נמצא בכל מקום בהשוואה למדינות אירופה, אבל יש הרבה לחם שטוח טוב בצפון סין, וגם באוזי (包子) (קנטונזית: באו) - לחמניות מנוהלות במילוי מילוי מתוק או מלוח - הן חלק בלתי נפרד מהן קנטונזית דים סאם ופופולרי גם במקומות אחרים בארץ. לחמניות ללא מילויים ידועות בשם מנטו (馒头 / 饅頭), והם מנת ארוחת בוקר פופולרית בצפון סין; ניתן להגיש את אלה מאודים או מטוגנים בשמן עמוק. מאכלים טיבטיים ואויגורים מכילים במידה רבה לחם שטוח הדומה לאלה בצפון הוֹדוּ וה המזרח התיכון.

למעט באזורי מיעוטים אתניים מסוימים כמו יונאן, טיבט, מונגוליה הפנימית ו שינג'יאנג, מַחלָבָה מוצרים אינם נפוצים במטבח הסיני המסורתי. עם הגלובליזציה, מוצרי חלב משולבים בכמה מזונות בשאר המדינה, כך שתוכלו לראות למשל באוזי ממולא עם פודינג, אך אלה נשארים יוצאים מן הכלל. מוצרי חלב מופיעים גם במקרים מעטים יותר במטבחים של הונג קונג, מקאו וטייוואן מאשר אלו של סין היבשתית בגלל השפעות מערביות חזקות יותר.

אחת הסיבות שמוצרי חלב אינם נפוצים היא שרוב המבוגרים הסינים אינם סובלים מלקטוז; חסר להם אנזים הנדרש לעיכול לקטוז (סוכר חלב), ולכן הוא מתעכל על ידי חיידקי המעי במקום, ויוצר גז. מנה גדולה של מוצרי חלב עלולה לפיכך לגרום לכאב ניכר ומבוכה רבה. מצב זה מופיע בפחות מ -10% מצפון אירופאים, אך מעל 90% מהאוכלוסייה בחלקים מאפריקה. סין נמצאת איפשהו בין לבין, ויש שינויים אזוריים ואתניים בשיעורים. יוגורט נפוץ למדי בסין; זה לא מייצר את הבעיה מכיוון שהחיידקים בה כבר פירקו את הלקטוז. באופן כללי קל יותר למצוא יוגורט מאשר חלב, וגבינה היא פריט יוקרתי יקר.

כלי אוכל

תמצאו בסין כל מיני מנות בשר, ירקות, טופו ואטריות. להלן מספר מנות ידועות ומובהקות:

- בודהה קופץ מעל הקיר (佛跳墙, fótiàoqiáng) - יקר פוז'ונס מרק עשוי סנפיר כריש (鱼翅, יוכי), אבלון ועוד מרכיבי פרימיום רבים שאינם צמחוניים. על פי האגדה, הריח היה כל כך טוב שנזיר בודהיסטי שכח את נדריו הצמחוניים וזינק מעל קיר המקדש כדי שיהיו לו. בדרך כלל צריך להזמין כמה ימים מראש בגלל זמן ההכנה הארוך.

- גובורו (锅 包 肉) - בשר חזיר חמוץ מתוק מ צפון מזרח סין.

- רגלי תרנגולת (鸡爪, jī zhuǎ) - בישלו הרבה דרכים שונות, רבים בסין רואים בהם את החלק הכי טעים בעוף. ידוע כטפרי עוף החול (凤爪 fuhng jáau בקנטונזית, fèng zhuǎ במנדרינית) באזורים דוברי קנטונזית, שם מדובר במנת דים סאם פופולרית והכי מכינים אותה ברוטב שעועית שחורה.

- מאפו טופו (麻 婆 豆腐, mápó dòufu) - א סצ'ואני מנת טופו ובשר חזיר טחון, חריף מאוד ובעל סצ'ואן קלאסי מאלה חריפות עקצנית / קהה.

- ברווז פקין (北京 烤鸭, Běijīng kǎoyā) - ברווז צלוי, המאכל המפורסם ביותר המאפיין בייג'ינג.

- טופו מסריח (臭豆腐, chòu dòufu) - בדיוק איך זה נשמע. לכמה אזורים שונים יש סוגים שונים, אם כי המפורסם ביותר הוא צ'אנגשה-סגנון, עשוי בלוקים מלבניים המושחרים מבחוץ. סגנונות בולטים אחרים של המנה כוללים שאוקסינג-סגנון ו נאנג'ינג-סִגְנוֹן. זו גם מנת רחוב פופולרית מאוד ב טייוואן, שם הוא זמין בסגנונות שונים.

- טופו ממולא (酿 豆腐, niàng dòufu במנדרין, נגיונג4 têu4 פו4 בהאקה) - מנת האקה, טופו מטוגן במילוי בשר, המכונה יונג טאו פו בדרום מזרח אסיה, אם כי לעתים קרובות שונה מאוד מהמקור.

- Xiǎolóngbāo (小笼 包) - כופתאות מלאות מרק קטנות מ שנחאי, ג'יאנגסו ו ג'ג'יאנג.

- חזיר חמוץ מתוק (咕噜 肉 gūlūròu במנדרין, gūlōuyuhk בקנטונזית) - מאכל קנטונזי, שהומצא כדי להתאים לחיך של האירופאים והאמריקאים שבסיסם בגואנגדונג במהלך המאה ה -19. אחת המנות הסיניות הפופולריות ביותר במדינות דוברות אנגלית.

- מרק חם וחמוץ (酸辣 汤 סונלה טאנג) - מרק סמיך ועמילני שעושים אותו חריף עם פלפלים אדומים וחמוץ עם חומץ. מומחיות של המטבח הסצ'ואני.

- חביתת צדפות (海 蛎 煎 hǎilì jiān או 蚝 煎 háo jiān) - מנה עשויה ביצים, צדפות טריות ועמילן בטטה, שמקורן ב דרום פוג'יאן ו צ'אושאן, אם כי עם וריאציות שונות. אולי הגרסא המפורסמת ביותר בעולם זה היא הגרסה הטאיוואנית שנמצאת בכל מקום בשווקי הלילה באי. וריאציות אחרות ניתן למצוא גם באזורים עם קהילות פזורות גדולות מהאזורים הנ"ל, כגון סינגפור, פנאנג ובנגקוק. מכונה 蚵仔煎 (ô-á-chiān) באזורים דוברי מינן (כולל טייוואן, שם כמעט לא ידוע שם המנדרינית), ו- 蠔 烙 (o5 לוה4) באזורים דוברי Teochew.

נודלס

מקורם של נודלס בסין: התיעוד המוקדם ביותר שנכתב עליהם נועד לפני כ -2,000 שנה, וראיות ארכיאולוגיות דווחו על צריכת אטריות לפני 4,000 שנה בלג'יה במזרח. צ'ינגהאי. לסינית אין מילה אחת לאטריות, במקום לחלק אותם ל מיין (面), עשוי מחיטה, ו בִּצָה (粉), עשוי מאורז או לפעמים מעמילנים אחרים. האטריות משתנות לפי אזור, עם מגוון מרכיבים, רוחביהן, אופן ההכנה והתוספות, אך בדרך כלל מוגשות עם סוג של בשר ו / או ירקות. הם עשויים להיות מוגשים עם מרק או יבש (עם רוטב בלבד).

הרטבים והטעמים המשמשים לאטריות כוללים רוטב סינגואי-חריף (麻辣, מאלה), רוטב שומשום (麻酱, מנג'יאנג), רוטב סויה (酱油 jiàngyóu), חומץ (醋, cù) ורבים אחרים.

- אטריות ביאנגבינג (

.svg/15px-Biang_(简体).svg.png)

.svg/15px-Biang_(简体).svg.png) 面, biángbiáng miàn) - אטריות עבות, רחבות, לעיסות בעבודת יד מ שאאנשי, ששמו כתוב עם דמות כה מסובכת ושימוש מועט עד שהיא אינה רשומה במילונים ולא ניתן להזין אותה ברוב המחשבים (לחץ על התו כדי לראות גרסה גדולה יותר). ייתכן שתראה אותם גם ברשימה 油泼 面 yóupō miàn בתפריטים שלא הצליחו להדפיס את התו כראוי.

面, biángbiáng miàn) - אטריות עבות, רחבות, לעיסות בעבודת יד מ שאאנשי, ששמו כתוב עם דמות כה מסובכת ושימוש מועט עד שהיא אינה רשומה במילונים ולא ניתן להזין אותה ברוב המחשבים (לחץ על התו כדי לראות גרסה גדולה יותר). ייתכן שתראה אותם גם ברשימה 油泼 面 yóupō miàn בתפריטים שלא הצליחו להדפיס את התו כראוי. - אטריות צ'ונגצ'ינג (重庆 小 面, Chóngqìng xiǎo miàn) - אטריות מתובלות-חריפות מוגשות בדרך כלל עם מרק, כנראה המנה המפורסמת ביותר מ צ'ונגצ'ינג יחד עם סיר חם.

- Dāndān miàn (担 担 面) - סצ'ואני אטריות דקות חריפות, מוגשות "יבשות" או עם מרק.

- אטריות מטוגנות (炒面, chǎo miàn ו- 炒粉 chǎo fěn או 河粉 héfěn) - המכונה בקרב אנשי סיני-מסעדות במדינות אחרות בשם "צ'או מיין"ו"כיף צ'או"אחרי ההצהרות הקנטונזיות שלהם, האטריות המוקפצות האלה משתנות לפי אזור. הן לא תמיד שמנות וכבדות כמו החומר שתמצאו במסעדות סיניות רבות בחו"ל. לא להתבלבל עם צ'ו פאן (炒饭), שהוא אורז מטוגן.

- אטריות יבשות חמות (热干面, règānmiàn), מנה פשוטה של אטריות עם רוטב, "יבשה" במובן שמוגשת ללא מרק. מומחיות של ווהאן, הוביי.

- אטריות חתוכות סכין (刀削面, dāoxiāo miàn) - מ שאנשי, לא דק אבל גם לא בדיוק רחב, מוגש עם מגוון רטבים. "ככל שאתה לעס אותם יותר, כך הם נעימים יותר."

- Lánzhōu lāmiàn (兰州 拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn), טרי לנזו-אטריות נשלפות ביד. ענף זה נשלט בכבדות על ידי בני הקבוצה האתית הוי (i) - חפשו מסעדה זעירה עם צוות לבוש מוסלמי, כובעים לבנים דמויי פאס על הגברים וצעיפי ראש על הנשים. אם אתה מחפש חלאל אוכל מחוץ לאזור שרוב הרוב המוסלמי, המסעדות האלה הן דבר טוב - לרבים יש שלטים המפרסמים "חלאל" (清真, qīngzhēn) בסינית או בערבית.

- ליאנגפי (凉皮), אטריות שטוחות המוגשות קרות, מקורן ב שאאנשי.

- תסתכל (拌面, bàn miàn) - אטריות דקות ויבשות עם רוטב.

- אטריות אריכות ימים (长寿 面, chángshòu miàn) הם מנת יום הולדת מסורתית, האטריות הארוכות המסמלות חיים ארוכים.

- לוסיפן (螺蛳 粉) - אטריות עם מרק חלזונות נהר מ גואנגשי.

- אטריות מעבר לגשר (过桥 米线, guò qiáo mǐxiàn) - מרק אטריות אורז מ יונאן.

- אטריות וונטון (云吞 面 yún tūn miàn) - מנה קנטונזית, המורכבת מאטריות ביצים דקות המוגשות במרק עם כופתאות שרימפס. וריאציות שונות של המנה קיימות בקרב הפזורה הקנטונזית ב דרום מזרח אסיה, אם כי לעתים קרובות שונה מאוד מהמקור.

חֲטִיפִים

סוגים שונים של אוכל סיני מספקים ארוחות קלות, מהירות, זולות, טעימות. אוכל רחובות וחטיפים שנמכרים מספקים ניידים ומחנויות חור-בקיר ניתן למצוא ברחבי הערים בסין, טוב במיוחד לארוחת בוקר או חטיף. מחוז וואנגפוג'ינג רחוב החטיפים בבייג'ינג הוא אזור בולט, אם הוא מתוייר, לאוכל רחוב. באזורים דוברי קנטונזית קוראים לספקי אוכל רחוב גאי בין דונג; מיזמים כאלה יכולים לצמוח לעסק מהותי כאשר הדוכנים רק "ניידים" במובן אוכל הרחוב המסורתי. בנוסף לספקי רחוב קטנים, ניתן למצוא חלק מהפריטים הללו בתפריט במסעדות, או בדלפק בחנויות נוחות כמו 7-Eleven. אוכלים מהירים שונים הזמינים ברחבי הארץ כוללים:

- באוזי (包子) - לחמניות מאודות ממולאות במילוי מתוק או מלוח כמו ירקות, בשר, רסק שעועית אדומה מתוקה, פודינג, או זרעי שומשום שחור

- מקלות בשר על המנגל (串 צ'ואן) מספקי רחוב. קל לזהות מכיוון שאפילו הדמות נראית כמו קבב! קבב טלה לוהט בסגנון שינג'יאנג (羊肉 串 yángròu chuàn) ידועים במיוחד.

- קונגי (粥 zhōu או 稀饭 xīfàn) - דייסת אורז. ה קנטונזית, Teochew ו מינן במיוחד אנשים העלו את המאכל הפשוט לכאורה הזה לצורת אמנות. לכל אחד מהם סגנונות ייחודיים וחגיגיים במיוחד.

- כדורי דגים (鱼丸 יואוון) - משחת דגים מעוצבת בצורת כדור, פופולרית בחלק גדול מחופי הים גואנגדונג ו פוג'יאן, כמו גם ב הונג קונג ו טייוואן. שתי ערים במיוחד מפורסמות בקרב סינים אתניים ברחבי העולם בזכות גרסאותיהם למנה זו; שאנטוכדורי דגים בסגנון הם בדרך כלל פשוטים ללא מילויים, ואילו פוז'וכדורי דגים בסגנון מלאים בדרך כלל בשר חזיר טחון.

- ג'יאנגבנג (煎饼), פנקייק ביצה שנכרך סביב קרקר עם רוטב, ולחילופין, רוטב צ'ילי.

- ג'יוזי (饺子), שאותם מתרגמים סינית כ"כופתאות ", פריטים דמויי רביולי מבושלים, מאודים או מטוגנים עם מגוון מילויים, מצרך מרכזי בצפון סין. אלה נמצאים ברחבי אסיה: מומוס, מנדו, גיוזה וג'יאוזי הם בעצם וריאציות של אותו הדבר.

- מנטו (馒头) - לחמניות מאודות מאודות, מוגשות לעתים קרובות ואוכלות עם חלב מרוכז.

- פודינג טופו (豆花, dòuhuā; או 豆腐 花, dòufuhuā) - בדרום סין פודינג רך זה בדרך כלל מתוק ואפשר להגיש אותו עם תוספות כמו שעועית אדומה או סירופ. בצפון סין, זה מלוח, עשוי ברוטב סויה, והוא נקרא לעתים קרובות dòufunǎo (豆腐 脑), פשוטו כמשמעו "מוח טופו". בטייוואן זה מתוק ויש בו הרבה נוזלים, מה שהופך אותו למשקה כמו אוכל.

- ווטו (窝窝头) - לחם תירס מאודה בצורת חרוט, פופולרי בצפון סין

- יוטיאו (油条) - פשוטו כמשמעו "רצועה שמנונית", המכונה "רוח רפואה מטוגנת בשמן עמוק" (油炸鬼) באזורים דוברי קנטונזית, מעין מאפה ארוך ושמנמן. יוטיאו עם חלב סויה הוא ארוחת הבוקר הטאיוואנית המובהקת, ואילו יוטיאו הוא תבלין נפוץ לקונג'ים במטבח הקנטונזי. האגדות אמרו כי ה- youtiao הוא מחאתו של מקובל על משתף פעולה שהכין גנרל פטריוטי למוות במהלך שושלת סונג הדרומית.

- ז'גאו (炸糕) - מעט מאפה מטוגן מתוק

- זונגזי (粽子) - כופתאות אורז דביקות גדולות עטופות עלי במבוק, נאכלות באופן מסורתי בפסטיבל סירת הדרקון (פסטיבל דואנו) בחודש מאי או יוני. בפסטיבל סירת הדרקון, תוכלו למצוא אותם למכירה בחנויות שמוכרות סוגים אחרים של כופתאות ולחמניות מאודות, ואולי אפילו תראו אותן בתקופות אחרות של השנה. המלית יכולה להיות מלוחה (咸 的 שיאן דה) עם בשר או ביצים, או מתוק (甜 的 tián de). המלוחים פופולאריים יותר בדרום סין, מתוקים בצפון.

תוכלו למצוא גם פריטים שונים, בדרך כלל מתוקים, מהמאפיות בכל מקום (面包店, miànbāodiàn). מגוון גדול של ממתקים ומאכלים מתוקים שנמצאים בסין נמכרים לרוב כחטיפים, ולא כקורס קינוחים לאחר הארוחה במסעדות כמו במערב.

פרי

- פיטאיה (火龙果, huǒlóngguǒ) הוא פרי מוזר למראה אם אינך מכיר אותו, עם עור ורוד, קוצים רכים ורודים או ירוקים שמציצים, בשר לבן או אדום וזרעים שחורים. הסוג עם בשר אדום מתוק ויקר יותר, אבל הסוג הלבן מרענן יותר.

- שיזף (枣, zǎo), המכונה לפעמים "התאריך הסיני", ככל הנראה בשל גודלו וצורתו, אך טעמו ומרקמו דומים יותר לתפוח. ישנם מספר סוגים שונים, וניתן לקנות אותם טריים או מיובשים. משמש לעתים קרובות להכנת מרקים קנטונזיים שונים.

- פרי קיווי (猕猴桃, míhóutáo, או לפעמים 奇异果, qíyìguǒ), יליד סין, שם תוכלו למצוא זנים רבים ושונים, קטנים כגדולים, עם צבע בשר שנע בין ירוק כהה לכתום. אנשים רבים מעולם לא טעמו קיווי בשל באמת - אם אתה רגיל לטייק קיווי שעליך לחתוך בסכין, עשה לעצמך טובה ונסה כזו טרייה, בשלה ובעונה.

- לונגן (龙眼, lóngyǎn, פשוטו כמשמעו "עין דרקון") דומה לליצ'י הידוע יותר (למטה), אך קטן יותר, עם טעם מעט בהיר יותר וקליפה חלקה יותר, צהובה בהירה או חומה. הוא נקצר בדרום סין מעט מאוחר יותר השנה מאשר ליצ'י, אך ניתן למצוא אותו למכירה גם בתקופות אחרות של השנה.

- ליצ'י (荔枝, lìzhī) הוא פרי עסיסי ומתוק להפליא עם טעם מבושם משהו, ובמיטבו כשקליפתו אדומה. הוא נבצר בסוף האביב ובתחילת הקיץ באזורים בדרום סין כגון גואנגדונג מָחוֹז.

- מנגוסטין (山竹, shānzhú), פרי סגול כהה בגודל של תפוח קטן. כדי לאכול אותו, סחט אותו מתחתית עד שהקליפה העבה נסדקת, ואז פתח אותו ואכל את הבשר הלבן והמתוק.

- שזיף (梅子, méizi; 李子, lǐzi) - שזיפים סיניים הם בדרך כלל קטנים יותר, קשים ומחמירים יותר משזיפים שתמצאו בצפון אמריקה. הם פופולריים טריים או מיובשים.

- יאנגמיי (杨梅) הוא סוג של שזיף, סגול עם משטח סתום עדין. הוא מתוק ובעל מרקם שקשה לתאר, כמו תות גרגרי או פטל.

- פּוֹמֶלוֹ (柚子, yòuzi) - נקרא לפעמים "אשכולית סינית", אך למעשה האשכולית היא צלב בין פרי הדר גדול זה לתפוז. בשרו מתוק יותר אך פחות עסיסי מאשכולית, מה שאומר שאפשר לאכול אותו בידיים ולא צריך סכין או כף. נקצרה בסתיו, פומלה גדולה מכדי שאדם אחד יוכל לאכול אותה, אז שתפו אותה עם בני לוויה.

- וומפי (黄皮, huángpí), פרי נוסף הדומה ללונגן ולליצ'י, אך בצורת ענבים ומעט טארט.

- אבטיח (西瓜, xīguā) זמין מאוד בקיץ. אבטיחים סיניים נוטים להיות כדוריים, ולא מוארכים בממד אחד.

בסין עגבניות ואבוקדו נחשבים לפירות. אבוקדו אינו נדיר, אך עגבניות נאכלות לעתים קרובות כחטיפים, כמרכיבים בקינוחים או מוקפצות עם ביצים מקושקשות.

מַשׁקָאוֹת

תה

.jpg/220px-China_-_Chengdu_4_-_green_tea_in_the_park_(135953545).jpg)

תה (茶, chá) ניתן למצוא כמובן במסעדות ובבתי תה ייעודיים. בנוסף לתה ה"מסודר "המסורתי יותר ללא חלב או סוכר, תה בועות עם כדורי חלב וטפיוקה (מוגש חם או קר) הוא פופולרי, ותוכלו למצוא תה קר מתוק בבקבוקים בחנויות ובמכונות אוטומטיות.

סין היא מקום הולדתו של תרבות התה, ובסיכון לקבוע את המובן מאליו, יש הרבה תה (茶 chá) בסין. תה ירוק (绿茶 lǜcháמוגש בחינם במסעדות מסוימות (תלוי באזור) או תמורת תשלום קטן. כמה סוגים נפוצים המוגשים הם:

- תה אבק שריפה (珠茶 zhūchá): תה ירוק שנקרא כך לא על פי הטעם אלא לאחר הופעת העלים המקובצים המשמשים לחלוטו (השם הסיני "תה פנינה" הוא די פואטי יותר)

- תה יסמין (茉莉花 茶 mòlihuachá): green tea scented with jasmine flowers

- oolong (烏龍 wūlóng): a half-fermented mountain tea.

However, specialist tea houses serve a vast variety of brews, ranging from the pale, delicate white tea (白茶 báichá) to the powerful fermented and aged pu'er tea (普洱茶 pǔ'ěrchá).

The price of tea in China is about the same as anywhere else, as it turns out. Like wine and other indulgences, a product that is any of well-known, high-quality or rare can be rather costly and one that is two or three of those can be amazingly expensive. As with wines, the cheapest stuff should usually be avoided and the high-priced products left to buyers who either are experts themselves or have expert advice, but there are many good choices in the middle price ranges.

Tea shops typically sell by the jin (斤 jīn, 500g, a little over an imperial pound); prices start around ¥50 a jin and there are many quite nice teas in the ¥100-300 range. Most shops will also have more expensive teas; prices up to ¥2,000 a jin are fairly common. The record price for top grade tea sold at auction was ¥9,000 per gram; that was for a rare da hong pao מ Mount Wuyi from a few bushes on a cliff, difficult to harvest and once reserved for the Emperor.

Various areas of China have famous teas, but the same type of tea will come in many different grades, much as there are many different burgundies at different costs. Hangzhou, near Shanghai, is famed for its "Dragon Well" (龙井 lóngjǐng) green tea. פוג'יאן ו Taiwan have the most famous oolong teas (乌龙茶 wūlóngchá), "Dark Red Robe" (大红袍 dàhóngpáo) from Mount Wuyi, "Iron Goddess of Mercy" (铁观音 tiěguānyīn) from Anxi, and "High Mountain Oolong" (高山烏龍 gāoshān wūlóng) from Taiwan. Pu'er in Yunnan has the most famous fully fermented tea, pǔ'ěrchá (普洱茶). This comes compressed into hard cakes, originally a packing method for transport by horse caravan to Burma and Tibet. The cakes are embossed with patterns; some people hang them up as wall decorations.

Most tea shops will be more than happy to let you sit down and try different varieties of tea. Tenfu Tea [1] is a national chain and in Beijing "Wu Yu Tai" is the one some locals say they favor.

Black tea, the type of tea most common in the West, is known in China as "red tea" (紅茶 hóngchá). While almost all Western teas are black teas, the converse isn't true, with many Chinese teas, including the famed Pǔ'ěr also falling into the "black tea" category.

Normal Chinese teas are always drunk neat, with the use of sugar or milk unknown. However, in some areas you will find Hong Kong style "milk tea" (奶茶 nǎichá) or Tibetan "butter tea". Taiwanese bubble tea (珍珠奶茶 Zhēnzhū Nǎichá) is also popular; the "bubbles" are balls of tapioca and milk or fruit are often mixed in.

קפה

קפה (咖啡 kāfēi) is becoming quite popular in urban China, though it can be quite difficult to find in smaller towns.

Several chains of coffee shops have branches in many cities, including Starbucks (星巴克), UBC Coffee (上岛咖啡), Ming Tien Coffee Language and SPR, which most Westerners consider the best of the bunch. All offer coffee, tea, and both Chinese and Western food, generally with good air conditioning, wireless Internet, and nice décor. In most locations they are priced at ¥15-40 or so a cup, but beware of airport locations which sometimes charge around ¥70.

There are many small independent coffee shops or local chains. These may also be high priced, but often they are somewhat cheaper than the big chains. Quality varies from excellent to abysmal.

For cheap coffee just to stave off withdrawal symptoms, there are several options. Go to a Western fast food chain (KFC, McD, etc.) for some ¥8 coffee. Alternately, almost any supermarket or convenience store will have both canned cold coffee and packets of instant Nescafé (usually pre-mixed with whitener and sugar) - just add hot water. It is common for travellers to carry a few packets to use in places like hotel rooms or on trains, where coffee may not be available but hot water almost always is.

Other non-alcoholic drinks

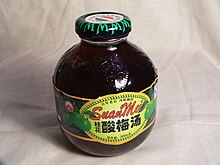

- Sour prune juice (酸梅汤 suānméitāng) – sweet and sour, and quite a bit tastier than what you might know as "prune juice" back home. Served at restaurants fairly often.

- Soymilk (豆浆 dòujiāng) – different from the stuff that's known as "soymilk" in Europe or the Americas. You can find it at some street food stalls and restaurants. The server may ask if you want it hot (热 rè) or cold (冷 lěng); otherwise the default is hot. Vegans and lactose-intolerant people beware: there are two different beverages in China that are translated as "soymilk": 豆浆 dòujiāng should be dairy-free, but 豆奶 dòunǎi may contain milk.

- Apple vinegar drink (苹果醋饮料 píngguǒ cù yǐnliào) – it might sound gross, but don't knock it till you try it! A sweetened carbonated drink made from vinegar; look for the brand 天地壹号 Tiāndì Yīhào.

- Herbal tea (凉茶 liáng chá) – a specialty of Guangdong. You can find sweet herbal tea drinks at supermarkets and convenience stores – look for the popular brands 王老吉 Wánglǎojí and 加多宝 Jiāduōbǎo. Or you can get the traditional, very bitter stuff at little shops where people buy it as a cold remedy.

- Winter melon punch (冬瓜茶 dōngguā chá) – a very sweet drink that originated in Taiwan, but has also spread to much of southern China and the overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

- Hot water (热水 rè shuǐ) – traditionally in China, ordinary water is drunk hot rather than cold. It may seem counterintuitive, but drinking hot water helps you sweat and thus cool off during the hot summer months. Nowadays there are plenty of people in China who drink cold water too, but if you happen to get a cold or feel ill during your trip, you're sure to hear lots of people advising you: "Drink more hot water."

Alcoholic

- ראה גם: China#Drink

- Báijiǔ (白酒) is very strong, clear grain liquor, made from sorghum and sometimes other grains depending on the region. The word "jiǔ" can be used for any alcoholic drink, but is often translated as "wine". Chinese may therefore call baijiu "white wine" in conversation, but "white lightning" would be a better translation, since it is generally 40% to 65% alcohol by volume.

- Baijiu will typically be served at banquets and festivals in tiny shot glasses. Toasts are ubiquitous at banquets or dinners on special occasions. Many Chinese consume baijiu only for this ceremonial purpose, though some — more in northern China than in the south — do drink it more often.

- Baijiu is definitely an acquired taste, but once the taste is acquired, it's quite fun to "ganbei" (toast) a glass or two at a banquet.

- Maotai (茅台 Máotái) or Moutai, made in גויג'ואו Province, is China's most famous brand of baijiu and China's national liquor. Made from sorghum, Maotai and its expensive cousins are well known for their strong fragrance and are actually sweeter than western clear liquors as the sorghum taste is preserved — in a way.

- Wuliangye (五粮液 Wǔliángyè) from Yibin, סצ'ואן is another premium type of baijiu. Its name literally translates as "five grains liquor", referring to the five different types of grains that go into its production, namely sorghum, glutinous rice, rice, wheat and maize. Some of its more premium grades are among the most expensive liquors in the world, retailing at several thousand US dollars per bottle.

- Kaoliang (高粱酒 gāoliángjiǔ) is a premium type of sorghum liquor most famously made on the island of Kinmen under the eponymous brand Kinmen Kaoling Liquor, which while just off the coast of Xiamen is controlled by Taiwan. Considered to be the national drink of Taiwan.

- The cheapest baijiu is the Beijing-brewed èrguōtóu (二锅头). It is most often seen in pocket-size 100 ml bottles which sell for around ¥5. It comes in two variants: 53% and 56% alcohol by volume. Ordering "xiǎo èr" (erguotou's diminutive nickname) will likely raise a few eyebrows and get a chuckle from working-class Chinese.

- There are many brands of baijiu, and as is the case with other types of liquor, both quality and price vary widely. Foreigners generally try only low-end or mid-range baijiu, and they are usually unimpressed; the taste is often compared to diesel fuel. However a liquor connoisseur may find high quality, expensive baijiu quite good.

.jpg/220px-Tsingtao_(28439950155).jpg)

- Beer (啤酒 píjiǔ) is common in China, especially the north. Beer is served in nearly every restaurant and sold in many grocery stores. The typical price is about ¥2.5-4 in a grocery store, ¥4-18 in a restaurant, around ¥10 in an ordinary bar, and ¥20-40 in a fancier bar. Most places outside of major cities serve beer at room temperature, regardless of season, though places that cater to tourists or expatriates have it cold. The most famous brand is Tsingtao (青島 Qīngdǎo) from Qingdao, which was at one point a German concession. Other brands abound and are generally light beers in a pilsner or lager style with 3-4% alcohol. This is comparable to many American beers, but weaker than the 5-6% beers found almost everywhere else. In addition to national brands, most cities will have one or more cheap local beers. Some companies (Tsingtao, Yanjing) also make a dark beer (黑啤酒 hēipíjiǔ). In some regions, beers from other parts of Asia are fairly common and tend to be popular with travellers — Filipino San Miguel in Guangdong, Singaporean Tiger in Hainan, and Laotian Beer Lao in Yunnan.

- Grape wine: Locally made grape wine (葡萄酒 pútáojiǔ) is common and much of it is reasonably priced, from ¥15 in a grocery store, about ¥100-150 in a fancy bar. However, most of the stuff bears only the faintest resemblance to Western wines. The Chinese like their wines red and very sweet, and they're typically served over ice or mixed with Sprite.

- Great Wall ו Dynasty are large brands with a number of wines at various prices; their cheaper (under ¥40) offerings generally do not impress Western wine drinkers, though some of their more expensive products are often found acceptable.

- China's most prominent wine-growing region is the area around Yantai. Changyu is perhaps its best-regarded brand: its founder introduced viticulture and winemaking to China in 1892. Some of their low end wines are a bit better than the competition.

- In addition to the aforementioned Changyu, if you're looking for a Chinese-made, Western-style wine, try to find these labels:

- Suntime[קישור מת], with a passable Cabernet Sauvignon

- Yizhu, in Yili and specializing in ice wine

- Les Champs D'or, French-owned and probably the best overall winery in China, from Xinjiang

- Imperial Horse and Xixia, from Ningxia

- Mogao Ice Wine, Gansu

- Castle Estates, Shandong

- Shangrila Estates, from Zhongdian, Yunnan

- Wines imported from Western countries can also be found, but they are often extremely expensive. For some wines, the price in China is more than three times what you would pay elsewhere.

- There are also several brands and types of rice wine. Most of these resemble a watery rice pudding, they are usually sweet and contain a minute amount of alcohol for taste. Travellers' reactions to them vary widely. These do not much resemble Japanese sake, the only rice wine well known in the West.

- סִינִית brandy (白兰地 báilándì) is excellent value; like grape wine or baijiu, prices start under ¥20 for 750 ml, but many Westerners find the brandies far more palatable. A ¥18-30 local brandy is not an over ¥200 imported brand-name cognac, but it is close enough that you should only buy the cognac if money doesn't matter. Expats debate the relative merits of brandies including Chinese brand Changyu. All are drinkable.

- The Chinese are also great fans of various supposedly medicinal liquors, which usually contain exotic herbs and/or animal parts. Some of these have prices in the normal range and include ingredients like ginseng. These can be palatable enough, if tending toward sweetness. Others, with unusual ingredients (snakes, turtles, bees, etc.) and steep price tags, are probably best left to those that enjoy them.

Restaurants

Many restaurants in China charge a cover charge of a few yuan per person.

If you don't know where to eat, a formula for success is to wander aimlessly outside of the touristy areas (it's safe), find a place full of locals, skip empty places and if you have no command of Mandarin or the local dialect, find a place with pictures of food on the wall or the menu that you can muddle your way through. Whilst you may be persuaded to order the more expensive items on the menu, ultimately what you want to order is your choice, and regardless of what you order, it is likely to be far more authentic and cheaper than the fare that is served at the tourist hot spots.

Ratings

Yelp is virtually unknown in China, while the Michelin Guide only covers Shanghai and Guangzhou, and is not taken very seriously by most Chinese people. Instead, most Chinese people rely on local website Dazhong Dianping for restaurant reviews and ratings. While it is a somewhat reliable way to search for good restaurants in your area, the downside is that it is only in Chinese. In Hong Kong, some people use Open Rice for restaurant reviews and ratings in Chinese and English.

Types of restaurants

Hot pot restaurants are popular in China. The way they work varies a bit, but in general you choose, buffet-style, from a selection of vegetables, meat, tofu, noodles, etc., and they cook what you chose into a soup or stew. At some you cook it yourself, fondue-style. These restaurants can be a good option for travellers who don't speak Chinese, though the phrases là (辣, "spicy"), bú là (不辣, "not spicy") and wēilà (微辣, "mildly spicy") may come in handy. You can identify many hot pot places from the racks of vegetables and meat waiting next to a stack of large bowls and tongs used to select them.

Cantonese cuisine is known internationally for dim sum (点心, diǎnxīn), a style of meal served at breakfast or lunch where a bunch of small dishes are served in baskets or plates. At a dim sum restaurant, the servers may bring out the dishes and show them around so you can select whatever looks good to you or you may instead be given a checkable list of dishes and a pen or pencil for checking the ones you want to order. As a general rule, Cantonese diners always order shrimp dumplings (虾饺, xiājiǎo in Mandarin, hāgáau in Cantonese) and pork dumplings (烧卖, shāomài in Mandarin, sīumáai in Cantonese) whenever they eat dim sum, even though they may vary the other dishes. This is because the two aforementioned dishes are considered to be so simple to make that all restaurants should be able to make them, and any restaurant that cannot make them well will probably not make the other more complex dishes well. Moreover, because they require minimal seasoning, it is believed that eating these two dishes will allow you to gauge the freshness of the restaurant's seafood and meat.

Big cities and places with big Buddhist temples often have Buddhist restaurants serving unique and delicious all-vegetarian food, certainly worth trying even if you love meat. Many of these are all-you-can-eat buffets, where you pay to get a tray, plate, bowl, spoon, cup, and chopsticks, which you can refill as many times as you want. (At others, especially in Taiwan, you pay by weight.) When you're finished you're expected to bus the table yourself. The cheapest of these vegetarian buffets have ordinary vegetable, tofu, and starch dishes for less than ¥20 per person; more expensive places may have elaborate mock meats and unique local herbs and vegetables. Look for the character 素 sù or 齋/斋 zhāi, the 卍 symbol, or restaurants attached to temples.

Chains

Western-style fast food has become popular. KFC (肯德基), McDonald's (麦当劳), Subway (赛百味) and Pizza Hut (必胜客) are ubiquitous, at least in mid-sized cities and above. Some of them have had to change or adapt their concepts for the Chinese market; Pizza Hut is a full-service sit down restaurant chain in China. There are a few Burger Kings (汉堡王), Domino's and Papa John's (棒约翰) as well but only in major cities. (The menu is of course adjusted to suit Chinese tastes – try taro pies at McDonald's or durian pizza at Pizza Hut.) Chinese chains are also widespread. These include Dicos (德克士)—chicken burgers, fries etc., cheaper than KFC and some say better—and Kung Fu (真功夫)—which has a more Chinese menu.

- Chuanqi Maocai (传奇冒菜 Chuánqí Màocài). Chengdu-style hot pot stew. Choose vegetables and meat and pay by weight. Inexpensive with plenty of Sichuan tingly-spicy flavor.

- Din Tai Fung (鼎泰丰 Dǐng Tài Fēng). Taiwanese chain specializing in Huaiyang cuisine, with multiple locations throughout mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as numerous overseas locations throughout East and Southeast Asia, and in far-flung places such as the United State, United Kingdom and Australia. Particularly known for their soup dumplings (小笼包) and egg fried rice (蛋炒饭). The original location on Xinyi Road in טייפה is a major tourist attraction; expect to queue for 2 hours or more during peak meal times.

- Green Tea (绿茶 Lǜ Chá). Hangzhou cuisine with mood lighting in an atmosphere that evokes ancient China. Perhaps you'll step over a curved stone bridge as you enter the restaurant, sit at a table perched in what looks like a small boat, or hear traditional music drift over from a guzheng player while you eat.

- Haidilao Hot Pot (海底捞 Hǎidǐlāo). Expensive hot pot chain famous for its exceptionally attentive and courteous service. Servers bow when you come in and go the extra mile to make sure you enjoy your meal.

- Little Sheep (小肥羊). A mid-range hot pot chain that has expanded beyond China to numerous overseas locations such as the United States, Canada and Australia. Based on Mongol cuisine—the chain is headquartered in Inner Mongolia. The specialty is mutton but there are other meats and vegetable ingredients for the hot pot on the menu as well. One type of hot pot is called Yuan Yang (鸳鸯锅 yuān yāng guō). The hot pot is separated into two halves, one half contains normal non-spicy soup stock and the other half contains má là (numbing spicy) soup stock.

- Yi Dian Dian (1㸃㸃 / 一点点 Yìdiǎndiǎn). Taiwanese milk tea chain that now has lots of branches in mainland China.

Ordering

Chinese restaurants often offer an overwhelming variety of dishes. Fortunately, most restaurants have picture menus with photos of each dish, so you are saved from despair facing a sea of characters. Starting from mid-range restaurants, there is also likely to be a more or less helpful English menu. Even with the pictures, the sheer amount of dishes can be overwhelming and their nature difficult to make out, so it is often useful to ask the waiter to recommend (推荐 tuījiàn) something. They will often do so on their own if they find you searching for a few minutes. The waiter will usually keep standing next to your table while you peruse the menu, so do not be unnerved by that.

The two-menu system where different menus are presented according to the skin color of a guest remains largely unheard of in China. Most restaurants only have one menu—the Chinese one. Learning some Chinese characters such as beef (牛), pork (猪), chicken (鸡), fish (鱼), stir-fried (炒), deep-fried (炸), braised (烧), baked or grilled (烤), soup (汤), rice (饭), or noodles (面) will take you a long way. As pork is the most common meat in Chinese cuisine, where a dish simply lists "meat" (肉), assume it is pork.

Dishes ordered in a restaurant are meant for sharing amongst the whole party. If one person is treating the rest, they usually take the initiative and order for everyone. In other cases, everyone in the party may recommend a dish. If you are with Chinese people, it is good manners to let them choose, but also fine to let them know your preferences.

If you are picking the dishes, the first question to consider is whether you want rice. Usually you do, because it helps to keep your bill manageable. However, real luxury lies in omitting the rice, and it can also be nice when you want to sample a lot of the dishes. Rice must usually be ordered separately and won’t be served if you don’t order it. It is not free but very cheap, just a few yuan a bowl.

For the dishes, if you are eating rice, the rule of thumb is to order at least as many dishes as there are people. Serving sizes differ from restaurant to restaurant. You can never go wrong with an extra plate of green vegetables; after that, use your judgment, look what other people are getting, or ask the waiter how big the servings are. If you are not eating rice, add dishes accordingly. If you are unsure, you can ask the waiter if they think you ordered enough (你觉得够吗? nǐ juéde gòu ma?).

You can order dishes simply by pointing at them in the menu, saying “this one” (这个 zhè ge). The way to order rice is to say how many bowls of rice you want (usually one per person): X碗米饭 (X wǎn mǐfàn), where X is yì, liǎng, sān, sì, etc. The waiter will repeat your order for your confirmation.

If you want to leave, call the waiter by shouting 服务员 (fúwùyuán), and ask for the bill (买单 mǎidān).

Eating alone

Traditional Chinese dining is made for groups, with lots of shared dishes on the table. This can make for a lonely experience and some restaurants might not know how to serve a single customer. It might however provide the right motivation to find other people (locals or fellow travellers) to eat with! But if you find yourself hungry and on your own, here are some tips:

Chinese-style fast food chains provide a good option for the lone traveller to get filled, and still eat Chinese style instead of western burgers. They usually have picture menus or picture displays above the counter, and offer set deals (套餐 tàocān) that are designed for eating alone. Usually, you receive a number, which is called out (in Chinese) when your dish is ready. Just wait at the area where the food is handed out – there will be a receipt or something on your tray stating your number. The price you pay for this convenience is that ingredients are not particularly fresh. It’s impossible to list all of the chains, and there is some regional variation, but you will generally recognize a store by a colourful, branded signboard. If you can’t find any, look around major train stations or in shopping areas. Department stores and shopping malls also generally have chain restaurants.

A tastier and cheaper way of eating on your own is street food, but exercise some caution regarding hygiene, and be aware that the quality of the ingredients (especially meat) at some stalls may be suspect. That said, as Chinese gourmands place an emphasis on freshness, there are also stalls that only use fresh ingredients to prepare their dishes if you know where to find them. Ask around and check the local wiki page to find out where to get street food in your city; often, there are snack streets or night markets full of stalls. If you can understand Chinese, food vlogs are very popular on Chinese social media, so those are a good option for finding fresh and tasty street food. Another food that can be consumed solo are noodle soups such as beef noodles (牛肉面 niúròumiàn), a dish that is ubiquitous in China and can also be found at many chain stores.

Even if it may be unusual to eat at a restaurant alone, you will not be thrown out and the staff will certainly try to suggest something for you.

Dietary restrictions

All about MSG Chinese food is sometimes negatively associated with its use of MSG. Should you be worried? בכלל לא. MSG, or monosodium glutamate, is a simple derivative of glutamic acid, an abundant amino acid that almost all living beings use. Just as adding sugar to a dish makes it sweeter and adding salt makes it saltier, adding MSG to a dish makes it more umami, or savory. Many natural foods have high amounts of glutamic acid, especially protein-rich foods like meat, eggs, poultry, sharp cheeses (especially Parmesan), and fish, as well as mushrooms, tomatoes, and seaweed. First isolated in 1908, within a few decades MSG became an additive in many foods such as dehydrated meat stock (bouillon cubes), sauces, ramen, and savory snacks, and a common ingredient in East Asian restaurants and home kitchens. Despite the widespread presence of glutamates and MSG in many common foods, a few Westerners believe they suffer from what they call "Chinese restaurant syndrome", a vague collection of symptoms that includes absurdities like "numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back", which they blame on the MSG added to Chinese food. This is bunk. It's not even possible to be allergic to glutamates or MSG, and no study has found a shred of evidence linking the eating of MSG or Chinese food to any such symptoms. If anyone has suffered these symptoms, it's probably psychological. As food critic Jeffrey Steingarten said, "If MSG is a problem, why doesn't everyone in China have a headache?" Put any thoughts about MSG out of your mind, and enjoy the food. |

People with dietary restrictions will have a hard time in China.

Halal food is hard to find outside areas with a significant Muslim population, but look for Lanzhou noodle (兰州拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn) restaurants, which may have a sign advertising "halal" in Arabic (حلال) or Chinese (清真 qīngzhēn).

Kosher food is virtually unknown, and pork is widely used in Chinese cooking (though restaurants can sometimes leave it out or substitute beef). Some major cities have a Chabad or other Jewish center which can provide kosher food or at least advice on finding it, though in the former case you'll probably have to make arrangements well in advance.

Specifically Hindu restaurants are virtually non-existent, though avoiding beef is straightforward, particularly if you can speak some Chinese, and there are plenty of other meat options to choose from.

For strict vegetarians, China may be a challenge, especially if you can't communicate very well in Chinese. You may discover that your noodle soup was made with meat broth, your hot pot was cooked in the same broth as everyone else's, or your stir-fried eggplant has tiny chunks of meat mixed in. If you're a little flexible or speak some Chinese, though, that goes a long way. Meat-based broths and sauces or small amounts of ground pork are common, even in otherwise vegetarian dishes, so always ask. Vegetable and tofu dishes are plentiful in Chinese cuisine, and noodles and rice are important staples. Most restaurants do have vegetable dishes—the challenge is to get past the language barrier to confirm that there isn't meat mixed in with the vegetables. Look for the character 素 sù, approximately meaning "vegetarian", especially in combinations like 素菜 sùcài ("vegetable dish"), 素食 sùshí ("vegetarian food"), and 素面 ("noodles with vegetables"). Buddhist restaurants (discussed above) are a delicious choice, as are hot pot places (though many use shared broth). One thing to watch out for, especially at hot pot, is "fish tofu" (鱼豆腐 yúdòufǔ), which can be hard to distinguish from actual tofu (豆腐 dòufǔ) without asking. As traditional Chinese cuisine does not make use of dairy products, non-dessert vegetarian food is almost always vegan. However, ensure that your dish does not contain eggs.

Awareness of food allergies (食物过敏 shíwù guòmǐn) is limited in China. If you can speak some Chinese, staff can usually answer whether food contains ingredients like peanuts or peanut oil, but asking for a dish to be prepared without the offending ingredient is unlikely to work. When in doubt, order something else. Szechuan peppercorn (花椒 huājiāo), used in Szechuan cuisine to produce its signature málà (麻辣) flavor, causes a tingly numbing sensation that can mask the onset of allergies, so you may want to avoid it, or wait longer after your first taste to decide if a dish is safe. Packaged food must be labeled if it contains milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, peanuts, tree nuts, wheat, or soy (the same as the U.S., likely due to how much food China exports there).

A serious soy (大豆 dàdòu) allergy is largely incompatible with Chinese food, as soy sauce (酱油 jiàngyóu) is used in many Chinese dishes. Keeping a strictgluten-free (不含麸质的 bùhán fūzhì de) diet while eating out is also close to impossible, as most common brands of soy sauce contain wheat; gluten-free products are not available except in expensive supermarkets targeted towards Western expatriates. If you can tolerate a small amount of gluten, you should be able to manage, especially in the south where there's more emphasis on rice and less on wheat. Peanuts (花生 huāshēng) and other nuts are easily noticed in some foods, but may be hidden inside bread, cookies, and desserts. Peanut oil (花生油 huāshēngyóu) ו sesame oil (麻油 máyóu or 芝麻油 zhīmayóu) are widely used for cooking, seasoning, and making flavored oils like chili oil, although they are usually highly refined and may be safe depending on the severity of your allergy. With the exception of the cuisines of some ethnic minorities such as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and Mongols, dairy is uncommon in Chinese cuisine, so lactose intolerant people should not have a problem unless you are travelling to ethnic-minority areas.

Respect

There's a stereotype that Chinese cuisine has no taboos and Chinese people will eat anything that moves, but a more accurate description is that food taboos vary by region, and people from one part of China may be grossed out by something that people in another province eat. Cantonese cuisine in particular has a reputation for including all sorts of animal species, including those considered exotic in most other countries or other parts of China. That said, the cuisine of Hong Kong and Macau, while also Cantonese, has somewhat more taboos than its mainland Chinese counterpart as a result of stronger Western influences; dog and cat meat, for instance, are illegal in Hong Kong and Macau.

ב מוסלמי communities, pork is taboo, while attitudes towards alcohol vary widely.

Etiquette

Table manners vary greatly depending on social class, but in general, while speaking loudly is common in cheap streetside eateries, guests are generally expected to behave in a more reserved manner when dining in more upmarket establishments. When eating in a group setting, it is generally impolite to pick up your utensils before the oldest or most senior person at the table has started eating.

China is the birthplace of chopsticks and unsurprisingly, much important etiquette relates to the use of chopsticks. While the Chinese are generally tolerant about table manners, you will most likely be seen as ill-mannered, annoying or offensive when using chopsticks in improper ways. Stick to the following rules:

- Communal chopsticks (公筷) are not always provided, so diners typically use their own chopsticks to transfer food to their bowl. While many foreigners consider this unhygienic, it is usually safe. It is acceptable to request communal chopsticks from the restaurant, although you may offend your host if you have been invited out.

- Once you pick a piece, you are obliged to take it. Don't put it back. Confucius says never leave someone with what you don't want.

- When someone is picking from a dish, don't try to cross over or go underneath their arms to pick from a dish further away. Wait until they finish picking.

- In most cases, a dish is not supposed to be picked simultaneously by more than one person. Don't try to compete with anyone to pick a piece from the same dish.

- Don't put your chopsticks vertically into your bowl of rice as it is reminiscent of incense sticks burning at the temple and carries the connotation of wishing death for those around you. Instead, place them across your bowl or on the chopstick rest, if provided.

- Don't drum your bowl or other dishware with chopsticks. Only beggars do it. People don't find it funny even if you're willing to satirically call yourself a beggar. Likewise, don't repeatedly tap your chopsticks against each other.

Other less important dining rules include:

- Whittling disposable chopsticks implies you think the restaurant is cheap. Avoid this at any but the lowest-end places, and even there, be discreet.

- Licking your chopsticks is considered low-class. Take a bite of your rice instead.

- All dishes are shared, similar to "family style" dining in North America. When you order anything, it's not just for you, it's for everyone. You're expected to consult others before you order a dish. You will usually be asked if there is anything you don't eat, although being overly picky is seen as annoying.

- Serve others before yourself, when it comes to things like rice and beverages that need to be served to everyone. אם אתה רוצה להגיש לעצמך עזרה שנייה של אורז, למשל, בדוק תחילה אם מישהו אחר נגמר והציע להגיש אותם קודם.

- השמעת רעשי סלורינג בזמן אכילה שכיחה אך יכולה להיחשב כבלתי הולמת, במיוחד בקרב משפחות משכילות. עם זאת, סלורינג, כמו "כוסות רוח" בעת טעימת תה, נתפס בעיני כמה גורמים כדרך להעצמת הטעם.

- זה נורמלי שהמארח או המארחת שלך שמים אוכל על הצלחת שלך. זו מחווה של טוב לב ואירוח. אם ברצונך לדחות, עשה זאת באופן שלא יפגע. למשל, עליכם להתעקש שהם יאכלו ושאתם מגישים בעצמכם.

- בספרי טיולים רבים נאמר כי ניקוי הצלחת מעיד על כך שהמארח שלכם לא האכיל אתכם טוב וירגיש לחצים להזמין אוכל נוסף. למעשה זה משתנה מבחינה אזורית, ובאופן כללי, סיום ארוחה כרוך באיזון עדין. ניקוי הצלחת שלך בדרך כלל יזמין יותר להגשה, ואילו השארת יותר מדי עשויה להיות סימן שלא אהבת את זה.

- כפיות משמשות כששותים מרקים או אוכלים מנות דקות או מימיות כמו דייסה, ולעתים כדי להגיש מכלי הגשה. אם אין כף, זה בסדר לשתות מרק ישירות מהקערה שלך.

- אוכל אצבעות נדיר במסעדות; באופן כללי אתה צפוי לאכול עם מקלות אכילה ו / או כף. עבור המזונות הנדירים שאתה אמור לאכול בידיים, ניתן לספק כפפות פלסטיק חד פעמיות.

- אם חתיכה חלקה מכדי לקחת, עשו זאת בעזרת כף; אל חודרים אותו בקצה החד של מקלות האכילה.

- ראשי דגים נחשבים למעדן ועלולים להציע לכם כאורח מכובד. למען האמת, בשר הלחיים במיני דגים מסוימים הוא מלוח במיוחד.

- אם בשולחן שלך יש סוזן עצלה, בדוק אם אין אף אחד שתופס אוכל לפני שאתה מסובב את סוזן העצלנית. כמו כן, לפני שהופכים את סוזן העצלנית, בדקו כדי לוודא שהכלים לא דופקים את כוסות התה או מקלות האכילה של אחרים שאולי הציבו אותה קרוב מדי לסוזן העצלנית.

רוב הסינים לא שמים רוטב סויה על קערת אורז מאודה. למעשה, לרוב רוטב סויה אינו זמין אפילו לשימוש הסועדים, מכיוון שהוא בעיקר מרכיב בישול, ולפעמים רק תבלין. אורז נועד להיות צד פשוט להבדיל מנות מלוחות טעימות, ולהגדיל את הארוחה עם עמילן.

מי משלם את החשבון

בסין, מסעדות ופאבים הם מקומות בילוי נפוצים מאוד וטיפול ממלא תפקיד חשוב בחברה.

בעוד שפיצול הצעת החוק מתחיל להתקבל על ידי צעירים, הטיפול הוא עדיין הנורמה, במיוחד כאשר הצדדים נמצאים במעמדות חברתיים שונים. מצופה מגברים לטפל בנשים, זקנים עד זוטרים, עשירים לעניים, מארחים לאורחים, מעמד הפועלים בכיתה ללא הכנסה (סטודנטים). חברים מאותה כיתה יעדיפו בדרך כלל לפצל את ההזדמנות לשלם, במקום לפצל את החשבון, כלומר "זה תורי, ואתה מתייחס לפעם הבאה."

נהוג לראות סינים מתחרים באופן אינטנסיבי על תשלום החשבון. מצופה ממך להילחם ולהגיד "תורי, אתה מתייחס אלי בפעם הבאה." המפסיד המחייך יאשים את הזוכה בכך שהוא אדיב מדי. כל הדרמות הללו, למרות שהן עדיין נפוצות בקרב כל הדורות ומשוחקות בדרך כלל בלב שלם, נהיות מעט פחות נפוצות בקרב סינים עירוניים צעירים יותר. בכל פעם שתסעדו עם סינית, יהיו לכם סיכויים הוגנים לטפל. עבור מטיילים בתקציב, החדשות הטובות הן כי הסינים נוטים להוטים לטפל בזרים, אם כי לא כדאי לצפות להרבה מסטודנטים וממעמד הפועלים העממי.

עם זאת, הסינים נוטים להיות סובלניים מאוד כלפי זרים. אם מתחשק לך ללכת הולנדית, נסה זאת. הם נוטים להאמין ש"כל הזרים מעדיפים ללכת הולנדית ". אם הם מנסים להתווכח, זה בדרך כלל אומר שהם מתעקשים לשלם גם עבור החשבון שלך, לא להפך.

מטה לא נהוג בסין, אם כי יש מסעדות שמוסיפות חיוב כיסוי, דמי שירות או "דמי תה" לחשבון. אם תנסה להשאיר טיפ, השרת עשוי לרוץ אחריך כדי להחזיר את הכסף ש"שכחת ".